A Patient’s Guide to Elbow Dislocations

Introduction

When the joint surfaces are separated—the term is dislocation. Elbow dislocations can be complete or partial, and usually occur after a trauma, such as a fall or accident. In a complete dislocation, the joint surfaces are completely separated. In a partial dislocation, the joint surfaces are only partly separated. A partial dislocation is also called a subluxation.

Anatomy

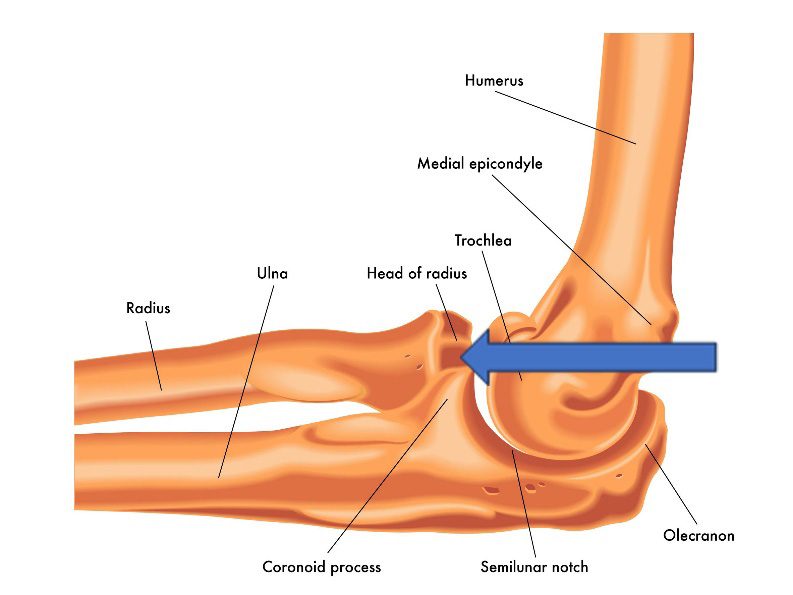

The elbow serves two distinct functions: 1) to bend and straighten 2) to turn the palm up and palm down. The elbow utilizes three bones in articulation to accomplish these purposes—humerus, ulna, and radius.

Lateral view of a right elbow demonstrating humerus, ulna, and radius. The radial head is identified with the arrow

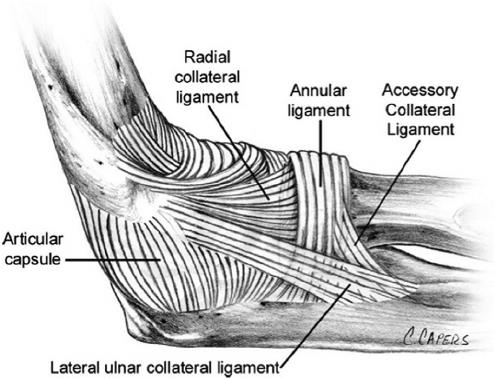

The bones of the elbow are held together by joint capsule, ligaments and tendons. As we age, the strength of both ligaments and bones decrease over time.

Ligaments of the elbow viewed from the lateral aspect

Diagnosis

Symptoms

Patients who experience distal humerus fractures present with pain, swelling and often bruising over time. There may be deformity of the arm dependent upon the degree of displacement of the dislocation

Physician Exam

After taking a history and noting your symptoms, a physical exam is then performed by the surgeon. The status of the vascular supply to the hand is observed. Similarly the sensation and motion of digits are noted. Although uncommon, dislocations in this area may embarrass vascular supply secondary to injury or swelling. Similarly, nerve function may be disrupted due to trauma or displacement of fractures.

Imaging

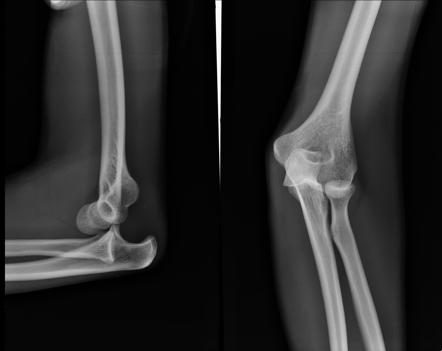

X-rays are indicated to determine the bones which have been injured and if there are any dislocations associated with the injury. X-rays may be taken from several angles to better delineate the fracture.

An anterior elbow dislocation viewed from the lateral view on the left, and from an anterior posterior view on the right.

In many cases, x-rays alone may adequately provide enough information to determine treatment. However, additional imaging for bone, such as computerized tomography (CT scan) may yield additional helpful information. If more concern is directed toward ligament or tendon injury, MRI imaging may be ordered.

Treatment

An elbow dislocation should be considered an emergency injury. The goal of immediate treatment of a dislocated elbow is to return the elbow to its normal alignment. The long- term goal is to restore function to the arm.

Nonsurgical Treatment

The normal alignment of the elbow can usually be restored in an emergency department at the hospital. Before this is done, sedatives and pain medications usually will be given. The act of restoring alignment to the elbow is called a reduction maneuver. It is done gently and slowly.

Normal alignment after the elbow has been reduced.

Simple elbow dislocations are treated by keeping the elbow immobile in a splint or sling for 1 to 3 weeks, followed by early motion exercises. If the elbow is kept immobile for a long time, the ability to move the elbow fully (range of motion) may be affected. Loss of elbow motion is common after injury. The most common losses are in extension and supination (palm up). Physical therapy or home based exercises can be helpful during this period of recovery.

Some people will never be able to fully open (extend) the arm, even after physical therapy. Fortunately, the elbow can work very well even without full range of motion. Once the elbow’s range of motion improves, the doctor or physical therapist may add a strengthening program. X-rays may be taken periodically while the elbow recovers to ensure that the bones of the elbow joint remains well aligned.

Operative Management

In a complex elbow dislocation, surgery may be necessary to restore bone alignment and repair ligaments. It can be difficult to realign a complex elbow dislocation and to keep the joint in line. At times local tissue may require augmentation with grafts either in an acute setting—or for late reconstruction

After surgery, the elbow may be protected with an external hinge. This device protects the elbow from dislocating again. If blood vessel or nerve injuries are associated with the elbow dislocation, additional surgery may be needed to repair the blood vessels and nerves and repair bone and ligament injuries. External fixators are often utilized in acute treatment of elbow instability cases—which remain unstable without this addition.

A hinged external fixator applied to the left elbow. Typically motion for the elbow begins with the fixator in place approximately two weeks after surgery. The fixator is then left in place for a total of six to ten weeks on average. Removal of the fixator may be done in an office or outpatient setting with local anesthesia.

Rehabilitation

After surgery the arm is immobilized in a splint to allow for wound healing. The ability to gain stable fixation determines the amount of motion allowed for the elbow, as well as the postoperative timing. Bracing may be used in the postoperative period to control motion and formal therapy is often a useful adjuvant for care. Patients report pain after surgery, but the pain generally improves as the soft tissues begin to heal. Initiation of therapy causes soreness for many patients.

Ligament healing requires approximately 16 weeks and many patients require months of therapy to reach maximum improvement. Improvement over the injury state occurs for most individuals resulting in a functional elbow. However, even under the best of circumstances–some limitation of motion, soreness, and stiffness may result. Arthritis associated with posttraumatic arthritis may result from these severe injuries. Other complications can include infection, nerve injury, nonunion of bones, and painful hardware.